for eight solo voices (SSAATTBB)

duration ca 5'

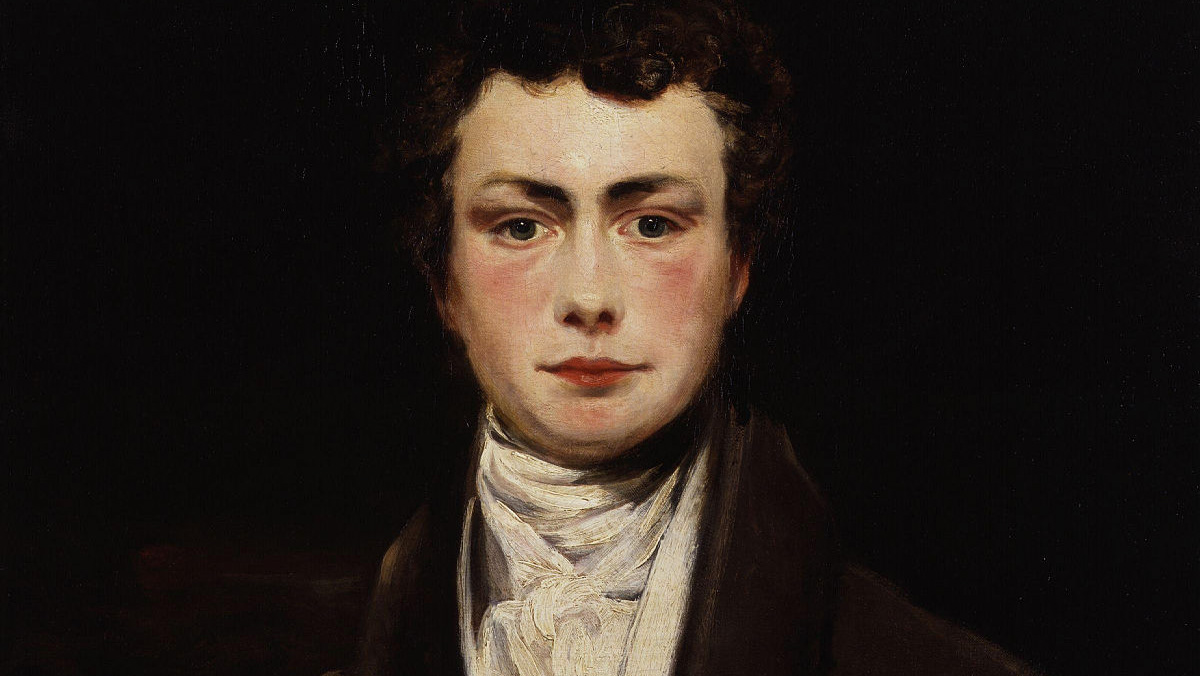

Patrick Pearse (1879-1916) is known as an Irish patriot, scholar, teacher and poet. He is perhaps most noted for his role as leader of the Republican forces in the Easter Rising of 1916. Pearse's motives were initially more concerned with the impact of English occupation on Irish culture rather than Irish Politics. In particular, he was an active Irish language revivalist, eschewing the dialect spoken in Dublin (predominantly Munster Irish) in order to seek the ‘real language’ which he believed to be Connemara Irish. This developed into Pearse’s vision of a ‘free Gaelic Ireland’, which soon evolved into the political extremism that brought about the rebellion.

Pearse wrote a number of papers and poems to express his intellectual and emotional feelings about the pursuit of Irish freedom. One of the finest examples of these is Mise Éire (1912), which typifies Pearse’s style and passion. Despite Pearse’s great respect for the sean-nós [old-style] singing and ancient Irish poetry which would have been cultivated during his many trips to the Connemara Gaeltacht, the style of Mise Éire is significantly short and to the point, contrary to more lengthy traditional offerings.

The poem draws on characters from Celtic mythology, a practice which was very much in vogue at the time. However, instead of portraying Ireland as a beautiful young woman, as for example in the play Cathleen Ní Houlihan (1902) by Lady Gregory and Yeats, Pearse opted to use the ‘Old Hag of Beare’. The Hag is a legendarily old ancestral mother who outlived many of her husbands. While interpretations of the Hag’s meaning throughout Celtic mythology are numerous and varied the general portrayal of the Hag is not a pretty one. Pearse’s inclusion of her in Mise Éire brings with it a degree of bitterness, a theme which flowed freely through Pearse’s literary output at the time. Pearse also uses the figure of Cú Chulainn, the archetypal Celtic war hero, as symbolic of the kind of figure that a faltering Irish culture needed to resist the occupying influences, to restore the traditional values of Irish life which Pearse would once again have experienced in Connemara. Interestingly, the figure of Cú Chulainn was eventually used to commemorate the Easter Rising both in a statute in the Dublin GPO and on the old Irish ten shilling coin (in 1966).

Mise Éire became the title of a 1959 documentary film directed by George Morrison documenting the foundations of the Irish Republic. The music for this film was composed by Seán Ó Riada (1931-1971), perhaps one of the most influential figures in the renaissance of Irish traditional music in the third quarter of the 20th century. This work, like a lot of Ó Riada’s output, combines traditional Irish material with orchestral arrangements. Ó Riada, using modes from the tradition much in the same way Vaughan-Williams had done with English folk music at the turn of the century, produced works which were essentially Irish-sounding, most notably the main theme from Mise Éire which has become widely recognised and subsequently re-used in similar contexts.

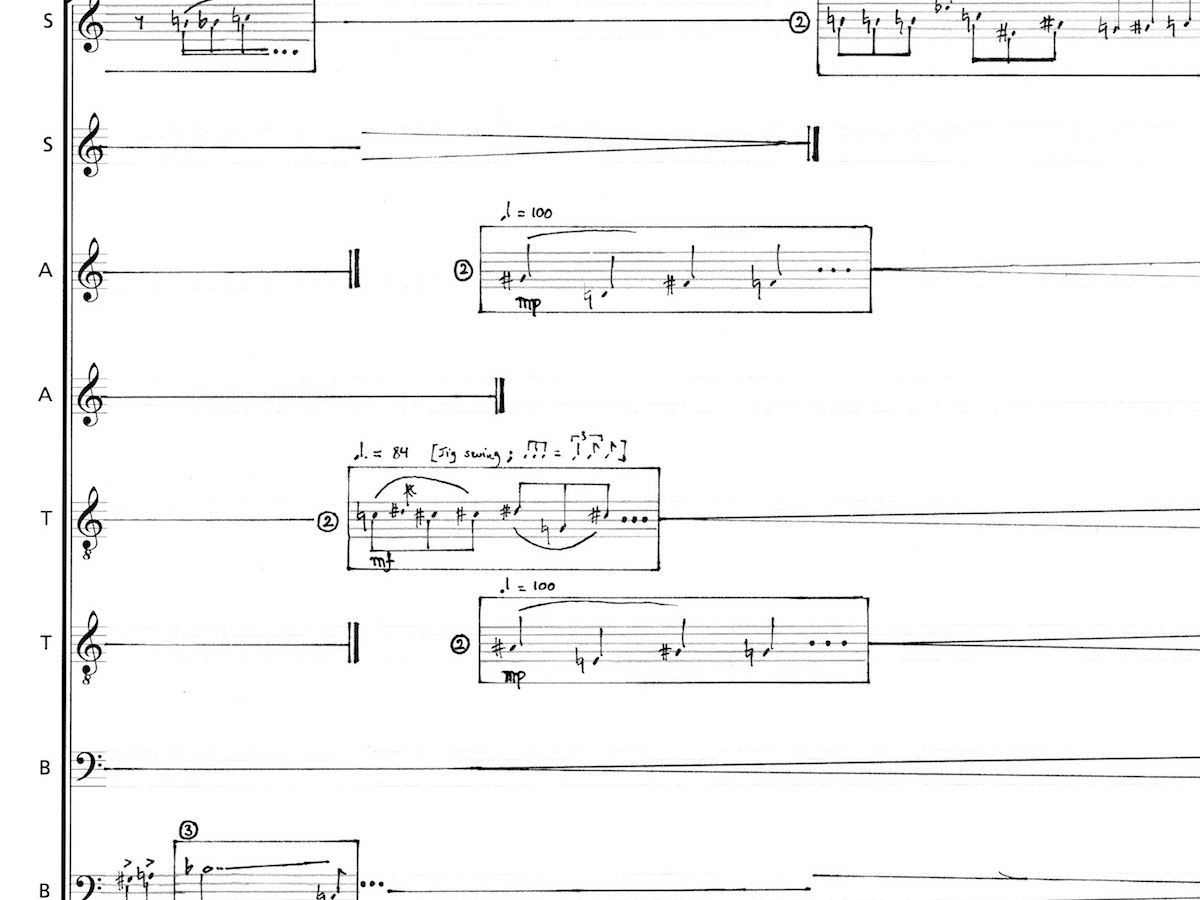

In my composition, I have attempted to take the ideas of the sean-nós style further in three ways. Firstly, I have endeavoured to incorporate some ornamentation typical of the style. This ornamentation is very elaborate and free in nature, which is reflected in the overall rhythm of the genre which can range from very non-metrical flows to defined rhythmic pulses. Secondly, I have used extended phrases requiring considerable breath control which are also typical of sean-nós songs. And lastly, I have endeavoured to draw from two modes which are, to me, so fundamental in Irish music: the dorian and mixolydian modes. (The mixolydian mode is not very common in tune structure, but can be neatly superimposed on many traditional tunes normally considered dorian). Individual melodic strands within the piece shift between these modes beginning on various primes to produce a very dense harmonic texture. Tension between these modes is created using microtones, which are undoubtedly a feature of very old Irish music, in particular sean-nós singing. Indeed, microtones in old Irish music may create entirely new ‘modes’ which need to be explored.

Past performances:

03.10.2011 — EXAUDI vocal ensemble, King’s Place, London, England, UK